The City Of Invention

The book reviews of UK children's author, Brian Keaney

The First Virtual City

Roger Crowley's account of the history of Venice is as readable as fiction. He is at his most gripping when detailing the events of the Fourth Crusade. After the sack of Constantinople he gets a little bogged down in the endless series of conflicts with the Genoese but the narrative picks up again with the appearance of the terrifying Sultan Mehmet and the inexorable advance of the Ottoman empire.

What is most fascinating about the history of Venice is the way that it invented itself and this is where Crowley is at his best. "One of the only Italian cities not to have existed in Roman times,' he observes, 'its inhabitants had created their antiquity out of theft and borrowings."

In Crowley's view Venice was always less of a geographical state and more a state of mind – "the first virtual city". As such it had enormous advantages over its competitors but was always dependent on factors outside its own control. So, when trade routes changed overnight with the discovery of a sea route to India, the network of trading relationships upon which its entire existence depended was suddenly obsolete.

Nevertheless, for hundreds of years a tiny city whose very existence seemed entirely improbable made an enormous impact upon the course of world history. Crowley's analysis of how they accomplished this astonishing feat is both illuminating and entertaining.

3

3

A Compelling Exploration Of Cultural Resonance

Colm Tóibín's new novel is an exploration of the stories of Clytemnestra, Orestes, and Electra all of whom appears in a number of Ancient Greek myths, perhaps most famously in the Oresteia of Aeschylus.

At the heart of the novel are three murders. Agamemnon, the leader of the Greek warriors setting out to attack Troy after the abduction of Helen, tricks his wife, Clytemnestra, into allowing their daughter, Iphigenia, to be sacrificed to the gods into exchange for a following wind for the ships conveying the invading army. Clytemnestra swears revenge on her husband and when he returns some years later, she murders him, with the help of her lover, Aegisthus. Subsequently, Orestes, her son, is removed from the palace, supposedly for his own safety, and held captive. He escapes from captivity, returns to the palace and kills his mother.

It takes a lot of nerve for a contemporary writer to tackle a story that generation after generation have loaded with significance. Tóibín rises to the challenge impressively and there is some wonderfully evocative writing e.g.

We are all hungry now. Food merely whets our appetite, it sharpens our teeth; meat makes us ravenous for more meat, as death is ravenous for more death. Murder makes us ravenous, fills the soul with satisfaction that is fierce and then luscious enough to create a taste for further satisfaction.

Unfortunately it is not all as good as this. There are other places where the writing loses its compelling quality and the energy drains away from the story.

Some of his narrative decisions puzzled me, such as the introduction of Leander, a friend who helps Orestes escape from captivity. In ancient versions of the story the very same role is performed by a character called Pylades. So I didn't understand why Tóibín felt it necessary to change this.

Perhaps he was highlighting the process by which stories intermingle and transform. That certainly seems to be the rationale for including The Children Of Lir, an ancient Irish story, in one of the storytelling sessions that Orestes witnesses while he is making his way homeward.

So the novel left me with unanswered questions. Nevertheless, I found it a compelling piece of storytelling and a wonderful exploration of cultural resonance.

The Glamour Of Power

Everyone knows the names of Julius Caesar, Augustus, Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and Nero and most people have heard at least some of the stories that surround them. But their iconic status has also served to make them unknowable. In this book Tom Holland sets out to redress the balance. The Julio-Claudians are still figures of epic proportion, imbued with terrible charisma and plunging headlong into corruption. But he brings them to life as individuals.

In doing so he also manages to conjure up the everyday reality of Ancient Rome, the religious fads, the fashions of the wealthy, the brutality of the military machine, the sexual obsessions and class prejudices, and, above all, the glamour of power that holds the whole city in its sway.

Tom Holland's voice is direct but always informed and authoritative. He combines a historian's feeling for pattern with a novelist's eye for detail. A riveting read.

Ultra-Violence And Male-Bonding

The loss of three legions in the Teutoburg Forest to a German ambush led by the treacherous Arminius was an event that had a huge impact on the Roman world. It is surprising, therefore, that there have been so few attempts to fictionalise it. In tackling such an important event for his debut Geraint Jones shows considerable boldness.

Unfortunately, he does not display an equal amount of historical awareness. The author is apparently a veteran of the Iraq war and it shows. This novel could easily be set in a modern day battlefield. The focus is all on graphic violence – of which there is a never-ending parade – and camaraderie. The sense of the period is entirely missing.

Indeed, authenticity is undermined by anachronism. There is nothing romantic about the sight of a legion, Jones observes. Well there wouldn't be, would there, this being the classical period? Yes, we know what he means but choice of words is important. Stories are built out of words.

Equally when describing a female innkeeper, he quips that hers was the face that launched a thousand ship, except that they were sailing in the opposite direction. Of course, you could justify the anachronism by arguing that the phrase pre-dated Marlowe. Nevertheless, it jars.

This is not a novel set in the Ancient World. It is a contemporary war-story about ultra violence and male bonding in which the protagonists just happen to be armed with swords.

4

4

The Indignities Of History

In Hannah's Dress Pascale Hugues, a French journalist living in Berlin, investigates the history of her street which at the beginning of the twentieth century was occupied by wealthy bourgeois families, many of them Jewish. Everything changed with the arrival of the Nazi party, of course. A few of the Jewish occupants managed to get out in time, to America or Israel, abandoning or selling properties and belongings for a pittance, but most ended up victims of the Nazi killing machine.

At the heart of the book is the poignant story of two friends, one of whom, Hannah, escapes to America. The other, who joins a queue for a permit to leave the country fifteen minutes too late, ends up being carted off on one of the special trains that took Jewish people away to their deaths.

The book is not only about the Jewish residents. Pascale Hugues finds out everything she can about the street and its residents, the ones who did well out of the Nazi era, the ones who moved into the vacated apartments the damage wreaked by Allied bombing, the architectural transformation as post-war Berliners tried to re-build the city and escape from their history, the businesses that came and went, the social and cultural changes and, with the collapse of the Berlin Wall, the flat where prog-rock band Tangerine Dream lived and where David Bowie briefly stayed, and the gentrification that has finally begun to endow the street with a modern version of its original status.

For me, the most interesting thing about the book, is the small details like the shopkeeper who assured her that the bomb damage was so great because it was orchestrated by Jews bent on revenge, or the bureaucratic labyrinth faced by those Jews who survived and struggled to reclaim some of their property or to seek compensation.

It is let down by a rather stilted translation. Tenses are badly handled and word-order still feels distinctly Germanic in places. Nevertheless, it's an impressive piece of social history. We are so used to contemplating the horrific scale of the Holocaust. By focusing on the little indignities, Pascal Hugues makes it feel so much more personal.

4

4

Divided Loyalties On Hadrian's Wall

Well-written, with a character-driven plot and a strong emotional narrative, Island Of Ghosts is the story of Ariantes, the leader of a group of Sarmatian warriors, barbarian auxiliaries brought to Britain to be stationed beside Hadrian's Wall.

Ariantes' arrives with divided loyalties. He and his followers were incorporated into the Roman army after a defeat and feelings are still raw on both sides. Regarded with contempt by the Roman military establishment, he struggles to keep his followers from a suicidal mutiny, a task made all the harder when indigenous Celtic tribes begin to exploit their divided loyalties.

I have often wondered how successfully barbarian warriors managed to integrate after entering the Roman army en bloc. The loss of one identity and the struggle to take on a new one must have been formidable. Gillian Bradshaw brings this rather academic question to life by focusing on the personal. There is plenty of careful research in this book but at its heart is a love story that is both convincing and moving. That is not something one finds too often in fiction set in the ancient world.

3

3

A Great Year For Historical Fiction

To co-incide with the 2017 Longlist for the the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction the Walter Scott Academy is recommending a further list of twenty books. My favourites are The North Water, The Ballroom and A Rising Man but I've read some of the others, too, and they were all very enjoyable.

The Walter Scott Prize Academy Recommends:

Carol Birch Orphans of the Carnival (Canongate)

Emily Bitto The Strays (Legend Press)

Jessie Burton The Muse (Picador)

Tracy Chevalier At the Edge of the Orchard (Borough Press)

Emma Donoghue The Wonder (Picador)

Susan Fletcher Let Me Tell you About a Man I Knew (Virago)

Anna Hope The Ballroom (Doubleday)

Lynne Katsukake The Translation of Love (Knopf Canada)

Lauri Kubuitsile The Scattering (Penguin South Africa)

Eowyn Ivey To the Bright Edge of the World (Tinder Press)

Ian McGuire The North Water (Scribner)

Abir Mukherjee A Rising Man (Harvill Secker)

S.J. Parris Conspiracy (HarperCollins)

Stephen Price By Gaslight (Oneworld)

Ralph Spurrier A Coin for the Hangman (Hookline Books)

Andrew Taylor The Ashes of London (HarperCollins)

Natasha Walter A Quiet Life (Borough Press)

A.N. Wilson Resolution (Atlantic)

Alissa York The Naturalist (Random House Canada)

Louisa Young Devotion (Borough Press)

3

3

Edwardian Essex In Very Slow Motion

It's book full of beautifully observed moments. Nevertheless, I struggled with it. There is almost no plot and I found it difficult to believe in the characters. In general they seemed altogether too modern. "I need a drink!" Cora announces after a difficult day, sounding like a twenty-first century woman who has been obliged to work too late at the office. I also found it difficult to like them. The narrator tells us that no-one could resist Cora. Well, I could. She got on my nerves. She was too much a creature of whimsy.

I can see that there are many fine things about this book but it put me off reading for several week.

READING PROGRESS

4

4

A Study In Maroon

Abir Mukherjee's debut crime novel, set in Calcutta in 1919, is instantly readable, wonderfully witty and very sharply observed. He's particularly good at setting, summoning up a vivid, if not-entirely respectful portrait of colonial India e.g.

"It was built in the style we like to call colonial neo-classic – all columns and cornices and shuttered windows. And it was painted maroon. If the Raj has a colour, it's maroon. Most government buildings, from police stations to post offices, are painted maroon. I expect there's a fat industrialist somewhere, Manchester or Birmingham probably, who got rich off the contract to produce a sea of maroon paint for all the buildings of the Raj."

Not long after his arrival in Calcutta, the protagonist, Captain Sam Wyndham of the Imperial Police Force, is confronted with a serious problem: the body of a sahib, dressed in black tie and tuxedo has turned up in the wrong part of town. Is this the beginning of an armed insurrection or was the victim part of something much more complicated? The investigation will see Sam nearly killed on more than one occasion as he struggles to uncover corruption at the very heart of British India.

With a jaundiced world-view as a result of four years in the trenches of World War One, a ruined marriage and a refusal to look the other way when his instinct tells him something is not right, Sam Wyndham has all the characteristics of a hard-boiled detective and A Rising Man looks set to be the start of a highly successful series.

One tiny thing that marred it for me. An Englishman in 1919 would not have said, "I was sat" or "We were stood" unless he came from Yorkshire. Nor would he talk about protesting something. He would have said "protesting against". Get on the case, editor!

4

4

Intrigue Amid The Icons

Set in Constantinople in the sixth century, this is the story of John, the illegitimate son of the empress Theodora. She was the eponymous bearkeeper's daughter, as well as being a former prostitute and actress who climbed her way out of poverty to become the most powerful woman in the world.

The story begins with John as a young man, arriving at the Byzantine court unexpectedly, not knowing whether his mother will acknowledge him , not even knowing whether she truly is his mother. It's a gamble that might have ended in his execution. Instead, Theodora welcomes him to the court and finds him a position. But on one condition: his identity must remain a secret.

This is a wonderfully engrossing novel. The characters are strongly depicted, the setting vividly evoked, the intrigues and dramas of the Byzantine court convincingly depicted. I devoured this book in a couple of days and all the time that I was reading it, I half-believed myself to be living amid the glittering mosaics and bejewelled icons of Justinian and Theodora's court.

2

2

Love and Death In Stalinist Russia

Set in Russia at the end of the Second World War, One Night In Winter begins with the violent death of two schoolchildren on a bridge in Moscow during the victory celebrations. But these are not two ordinary young people, they are children of the top Bolshevik rulers and their unexplained deaths set off an inquiry that will see their friends and teachers incarcerated in the Lubianka and their families destroyed.

Atmospheric, cleverly-plotted, and grippingly narrated, this is a horribly convincing depiction of the senseless and brutal tyranny that Stalin generated. But it's also a tribute to the human spirit for even in the such a dark story there is room for generosity and love

There were times when I had to put this book aside because the tension became unbearable. But I never put it out of my thoughts. Wonderful storytelling.

2

2

Narrative History At Its Best

Tom Holland's account of Early Medieval Europe has two main themes: the impact of the millennium on a society conditioned to expect the end of the world as described in the Book of Revelation; and the power struggle between the papacy and the Holy Roman emperor that culminated in the Investiture Climax and saw an emperor excommunicated and a pope imprisoned in the Vatican.

Holland's argument that the battle between emperor and pope, a conflict given greater urgency by the imminent arrival of Antichrist, laid the foundations for the birth of modern Europe is perhaps a little strained but it's worth it for the sheer panache with which he romps through Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

The sweep of the narrative is impressive, taking in events from Trondheim, to Jerusalem via Saxony, Cordoba and all stations to Constantinople, and the style is distinctly upbeat. At times almost taking on the voice of the characters, he is determined to convey what it felt like to be caught up in the events he describes.

You either like this approach or you don't - I read a distinctly sniffy review in The Telegraph by the historian, Noel Malcolm. But I couldn't put this book down. I found Holland's delight in the period completely infectious and I read the whole thing in about three days, neglecting all sorts of important jobs in the process. This is popular narrative history at its very best

2

2

The Context Of Renaissance Art

Geraldine Johnson's no-nonsense approach to Renaissance art contrasts the very different contexts in which Renaissance paintings, sculpture and crafted objects can be viewed. On the one hand she examines attitudes at the time: the very specific demands of the patrons who commissioned these works, and the uses to which the works were put, whether devotional, political, familial or domestic. On the other hand she considers the reverence with which the same objects are regarded nowadays by gallery-goers gazing through a post-Romantic lens in which the artist is seen as a creative genius in conflict with the world, giving expression to his troubled personality through his art

The scope of the book is limited by the parameters of the series in which it belongs. Nevertheless, Johnson does an excellent job, focusing on a series of individual artworks and outlining how they embody the economic, religious and political forces of the time. Clear, precise and informed.

1

1

Arrogance And Innocence

Two decades after Cass Wheeler, a hugely successful British singer-songwriter, retired abruptly from the music business, she is preparing to break her silence and release simultaneously an album of new material alongside an album of her greatest hits. The narrative of Laura Barnett's novel is structured around a day that Cass spends listening to each of the chosen tracks for her Greatest Hits album and remembering the events that inspired them.

Cass's reminiscences stretch right back to the early days of her career and Barnett does a very good job of evoking the heady sense of freedom of the nineteen seventies as the structures of post-war Britain, breached by the cultural explosion of the sixties, begin to crumble away, revealing a world where anything seems possible.

Unfortunately for Cass, the promises that a life of music seemed to offer turn out to be hollow: marital breakdown, the incompatibility of motherhood and the music business, and the mental illness of her daughter all conspire to turn her dream of unfettered creativity into a nightmare of recrimination.

It's an immensely readable novel. For me, however, the weak link is the lyrics with which each new section begins. Significant claims are made for them as the kind of songs that might speak to a generation but I wasn't entirely convinced. But this is no more than a quibble, amply compensated by the strongly drawn personality of Cass - flawed, damaged but always struggling towards redemption - and by the portrait of an era, already almost forgotten, full of arrogance, enthusiasm and a naïve kind of innocence.

1

1

A Compelling Study Of Child Abuse

Set at the beginning of the twentieth century in Ireland, The Wonder is the story of Lib Wright, an English nurse who, having learned her trade in the Crimea under Florence Nightingale, takes up a position in rural Ireland watching over eleven year old Anna O'Donnell, a girl who has supposedly been existing without food for several months and is now being talked of as a saint by the local community.

Lib is entirely sceptical of such claims and scathing in her judgement of the Irish and their religion. Determined to unveil a hoax she watches the girl like a hawk but gradually comes to understand that, whether or not Anna was secretly eating before her arrival, she is certainly not doing so now. As a consequence, Lib finds herself presiding over the slow starvation of a child, an atrocity in which the girl's family and her entire community are complicit.

Exchanging her scorn for pity, Lib tries desperately to change the girl's mind-set and persuade her to choose life instead of death. But Anna remains resolute and Lib struggles to understand what lies at the root of such implacable religiosity?

I wasn't always convinced by Emma Donoghue's portrait of the local Irish Catholic community which sometimes felt one-sided, even allowing for its portrayal through the lens of Lib's self-important Anglophile gaze. Moreover, the end, when it came, felt a little hurried.

A detailed chronicle of a young girl's self-inflicted starvation, The Wonder is not an easy book to read. More than once I had to set it aside for a day or two as I struggled with the emotions it evoked. Nevertheless, this is a compelling study of child-abuse so embedded within a community as to be invisible to victim and perpetrator alike.

4

4

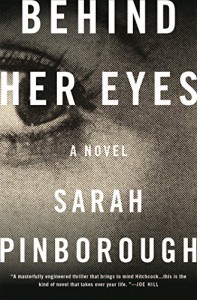

Made For The Market

If you were looking for a definition of a high-concept book, then look no further. Behind Her Eyes is as high-concept as it gets. A clever, plot-driven woman-in-jeopardy thriller with a paranormal twist, written in an easy-to-read confessional style and aimed directly at the thirty-something female reader, it hooks you into the story from the very first page.

For me, however, the lack of depth to the characters was the book's fatal flaw, particularly the villainous Adele who leads Louise, the victim, by the nose. In place of characterisation we get a great deal of coy pre-figuring of the if-only-she-knew-what-I had-in-store-for-her variety which quickly started to get on my nerves. But then, as a sixty something male, I'm not the target readership.

The ending took a little longer to arrive than I wanted. When it did come I thought it was going to be just as I had expected and at first that was exactly how it seemed Then came the final very neat and entirely unpredicted twist. I have to take my hat off to the author: it's a very well crafted ending but not an emotionally satisfying one. This is one of those books that ends with a shudder rather than a sigh of relief. I didn't enjoy that.

It's very much made for the market: a dash of Gone Girl, a splash of Before I Go To Sleep, a hint of Girl On A Train and then a little bit of mumbo-jumbo thrown in for good luck. But it's extremely well done. Not profound or meaningful just ingenious and entertaining.

2

2

1

1